Sealvation

Purpose-driven scientists and an army of volunteers at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Mammal Rescue Centre work together to perform some of the world's most popular rehabilitations.

The Marine Mammal Rescue Centre (MMR) takes in about 120 different animals over the course of a given year, including otters, sea lions, and cetaceans such as harbour porpoises. However, the vast majority of their patients are harbour seals. Located on the docks at the end of Main Street, across the water from the port, the MMR is operated by the Vancouver Aquarium.

Their hotline, 604-258-SEAL, operates year-round. The team at the MMR will drive up and down the B.C. coastline responding to calls about abandoned pups or injured otters and seals, or in some instances, sea lions who have been trapped or entangled in fishing nets or various other debris. Some of the animals saved by the MMR aren't fit to be released back into the wild due to a long-term injury, typically blindness or immobility. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans works closely with the MMR, and they make the final call on whether an animal will go back to nature or get looked after at a facility like the Vancouver Aquarium. The Vancouver Aquarium has trainers that specialize in the welfare of rehabilitated marine mammals. Stellar sea lions Rogue and Natoa are pictured here.

Angelica Kung, a Registered Veterinary Technologist at the MMR, dreamed of being in this line of work for a long time. She explained how the onboarding process works (for the animals): first, they're evaluated by the centre's veterinary team, and a treatment plan is drawn up. Then, they're quarantined for up to two weeks in the enclosures behind Angelica to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Once they're deemed healthy enough, they graduate to progressively larger pools with other patients of the same species to learn how to compete for food.

The team's days start early, especially in the wake of spring's pupping season when they see the greatest influx of inpatients. Many baby harbour seals are either abandoned by their mothers or fail to thrive because they were left to their own devices too early and weren't at the stage where they were ready to start hunting (some pups haven't even grown teeth by the time they've been abandoned). The MMR's tanks are full to bursting then, and its facilities are packed with volunteers. The winter season is much slower — there hasn't been a newly admitted animal since September, whereas July saw 54.

The MMR's well-equipped veterinary lab is a lynchpin of the rehabilitation process. With oxygen tanks, respirators, heart monitors and more, it's where the animals come in to get treatments and x-rays. Its long-time veterinarian, Dr. Martin Haulena, has made important advances in the realm of anesthesia here — the MMR uses his proprietary blend to safely sedate sea lions during dangerous rescue missions when the animals would otherwise be liable to hurt the team or themselves in their distress.

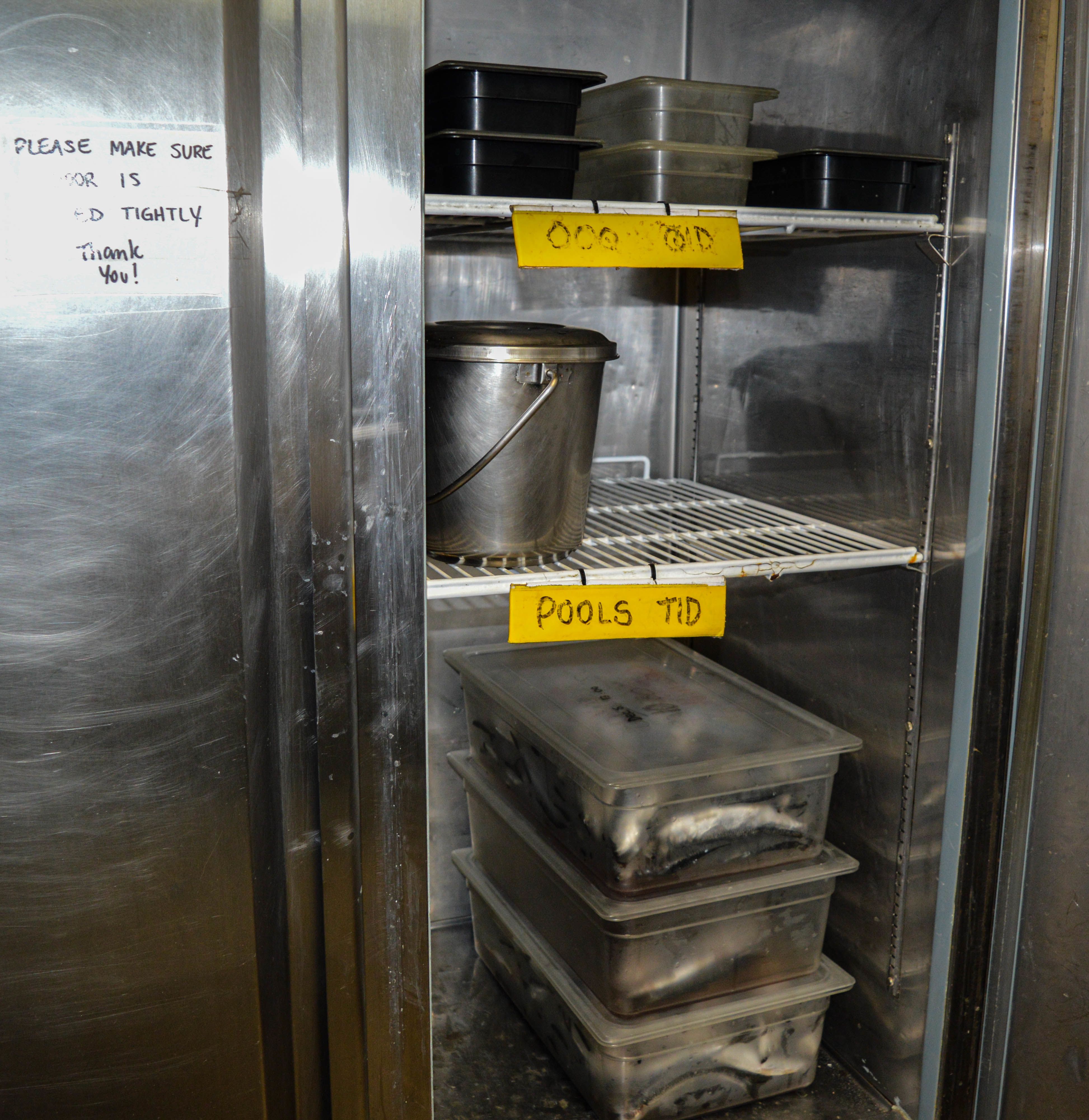

When a baby first arrives, depending on their age, they might be tube-fed for up to a month. After that, their diet takes a sharp turn to the pescetarian. Industrial fridges are heavily stocked with herring, and the animals learn valuable survival lessons as they jockey for their meals in the larger pools, growing stronger and more skillful in their "hunting" as a result of the competition.

Unfortunately, there's less glamorous work than preparing fish — a lot of bureaucracy needs to be attended to in order to make sure operations can keep running smoothly. On top of the run-of-the-mill paperwork, the MMR is going through the process of becoming a not-for-profit so that it can start accepting donations from its massive following. Its Instagram account has 128,000 followers, and its Facebook page has over 140,000 likes — their posts can sometimes garner millions of likes, but with the 'for-profit' status that was thrust on them when the Vancouver Aquarium was sold to private interests in 2021, they can't capitalize on their rabid fanbase. MMR manager Lindsaye Akhurst recalled how, at the height of the pandemic, an orphaned baby otter whose rehabilitation at the MMR was being live-streamed "won over the world." (Joey's adorable solicitations also brought in tens of thousands of dollars in donation money at a time when the Aquarium couldn't welcome guests.)

"We had millions and millions of people watching," Akhurst said. "He really honestly saved people's lives, having that live feed. People would just watch it constantly. And then this community came from that."

"This community" refers to Joey's most loyal disciples: the self-branded 'Meepers.' And in September, now that travel isn't actively discouraged, they descended on the Vancouver Aquarium for the first-ever MeepCon. Jessica DeBenedetto and Joey were there to welcome them.

Release day is a big deal for the MMR: the culmination of all their hard work, it signifies that they've achieved the best possible outcome for their patients. It's an emotional event, and they get their volunteers out to watch as a thank-you for their efforts. Howe Sound and Porteau Cove (pictured) are popular release locations.

The areas where the animals are released are chosen carefully — they can't be too busy or overpopulated, and they need to have a strong, diverse ecosystem that can support their new residents while they get their bearings. They used to aim to release animals near where they were found, but the practice was discontinued when tracking data revealed that the animals took off in random directions no matter where they were let go.

Akhurst says that according to MMR statistics, animals released from their care thrive in the wild at the same clip as their all-natural cousins.

Mission accomplished.